|

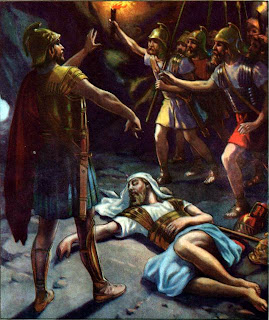

| Nathan confronts David |

(This homily was given on February 27, 2022 at St. Pius X Church, Westerly, R.I., by Fr. Raymond Suriani. Read Sirach 27:4-7; Psalm 92:2-16; 1 Corinthians 15:54-58; Luke 6:39-45.)

[For the audio version of this homily, click here: Eighth Sunday 2022]

You

could call it the “David Syndrome”—named after David, the second king of

Israel. It’s what Jesus is talking about

in our gospel reading today from Luke 6, in that section where he says, ”Why do you notice the splinter in your brother’s eye,

but do not perceive the wooden beam [i.e., the plank]

in your own? How can you say to your brother, ‘Brother, let me remove that splinter in your eye,’

when you do not even notice the wooden beam in

your own eye?”

As

I said, this syndrome—this disorder—is named for King David, because this is

precisely where he was at after he sinned with Bathsheba.

Most

of us know the story. David was out taking

a stroll on his rooftop veranda one evening and he spotted a young woman

bathing off in the distance. So he

invited her over to his place for a little “coffee-and”. Not surprisingly, it was the “and” that got

him into trouble. One thing led to

another (as the old saying goes), and the woman—Bathsheba—ended up pregnant.

Now

David could have repented and ended things right there, but instead he made the

decision to take matters into his own hands and to try to conceal his sin. He called Bathsheba’s husband, Uriah the

Hittite, home from battle and tried to get him to go home. He wanted Uriah to sleep with his wife, and

thus to think that he was the father of the child. But Uriah refused to go. And it was right for him to refuse because at

the time the nation was at war, and Uriah was a good soldier. Good soldiers in Israel weren’t supposed to

go home to their families when a war was going on.

So

David arranged to have Uriah killed. He

instructed the leader of his army, Joab, to put Uriah on the front lines of the

battle, and then to pull back from him at a certain point, so that Uriah would be

exposed to enemy attack—a “sitting duck,” so to speak. Well Joab, unfortunately, did what David

commanded him to do, and Uriah was, indeed, killed.

So

there was David—guilty of two deadly (what we today would call “mortal”)

sins—and yet he felt absolutely, positively no guilt whatsoever—about any of it! For him, life was great. He had a new wife (he ended up marrying Bathsheba)

and a new son. And in his kingdom, it

was business as usual.

Until

he was presented with a problem—a problem that supposedly involved someone

else. The prophet Nathan, inspired

by the Spirit, came to David one day and said, “David, I need your help. I’m

trying to figure out how to judge this particular case. There were two men in a certain town; one was

really, really rich, the other, unfortunately, was really, really poor. The rich man had lots and lots of flocks and

herds (too numerous to count); whereas the poor guy had just one little lamb

that he had bought with the little money he had. But he loved that lamb—and so

did his children. It was part of their

family. That is, until the day the rich

man stole the lamb from the poor man and his family, and cooked it up as a meal

for one of his houseguests. He could

have chosen one of his own lambs to feed his friend (he had thousands to choose

from), but he refused to do that. What

do you think about that man, David?

What’s your opinion?”

David

got angry and said, “As the Lord lives, the man who has done this deserves to

die! He should be executed!”

Nathan

said, “Well, that’s very interesting, David, because YOU ARE THAT MAN!!!”

That

was the moment David realized that he had a plank sticking in his eye—and a

pretty big one at that. It was also the

moment when he began the process of removing the plank. Thankfully it did not take long for the king

to admit his sin to Nathan. In fact, the

very first words that came out of David’s mouth after Nathan confronted him

were the words, “I have sinned against the Lord.” Later on David would

express his repentance in the 51st psalm when he wrote: “Have mercy

on me, O God, in your kindness; in your compassion blot out my offence. O wash me more and more from my guilt, and

cleanse me from my sin.”

Hopefully

it’s now clear: the “David Syndrome” is the tendency we all have to see the

sins of other people more clearly than we see our own. David saw the sin of the rich man in Nathan’s

story very clearly, but he was blind to his own. It reminds me of the little story I read this

past week in a commentary on today’s readings.

Some of you probably have heard this before. It’s about 4 monks who had taken a vow of

silence. All four of them were walking

down the road one day, when one of them stubbed his toe on a rock. He said, “Ow!” The second turned to him and said, “You

idiot! You broke your vow of

silence!” The third said to the second,

”You’re a bigger idiot than he is; you broke your vow of silence in telling him

that he broke his!” The fourth one just

smiled and said, “I’m the only one who didn’t.”

Here

we have four men, each of whom saw the faults of the other three more clearly

than he saw his own.

That’s

fallen human nature; that’s the “David Syndrome.”

I

think it’s providential that we have this particular gospel reading on the

Sunday before Lent begins. (Yes, believe

it or not, this coming Wednesday is Ash Wednesday!)

Lent

is a time of year when we should focus in a special way on the “planks” in our

eyes: the planks that we, like David, tend not to be aware of—or that we may tend

to ignore. That requires some

introspection; that requires some honest soul-searching, which in Catholic

terms is commonly referred to as an “examination of conscience.”

Examining

our consciences is actually something we should get in the habit of doing every

day of the year. If King David had

examined his conscience after he committed adultery with Bathsheba, perhaps he

wouldn’t have added murder to the list of serious sins he needed to repent

of.

Ordinarily,

planks are removed for us in the sacrament of Reconciliation—even big planks

like David’s. Hopefully we will all make

the effort to get to confession at least once during the upcoming Lenten season. (You’ll notice in the bulletin that Fr Najim

has added a few more confession times during the weeks of Lent to make it more

convenient for you to get there.)

All

that having been said, my prayer for all of you is that this year you will have,

not only a happy Easter, but also (and even more importantly) a “plank-free”

Easter!